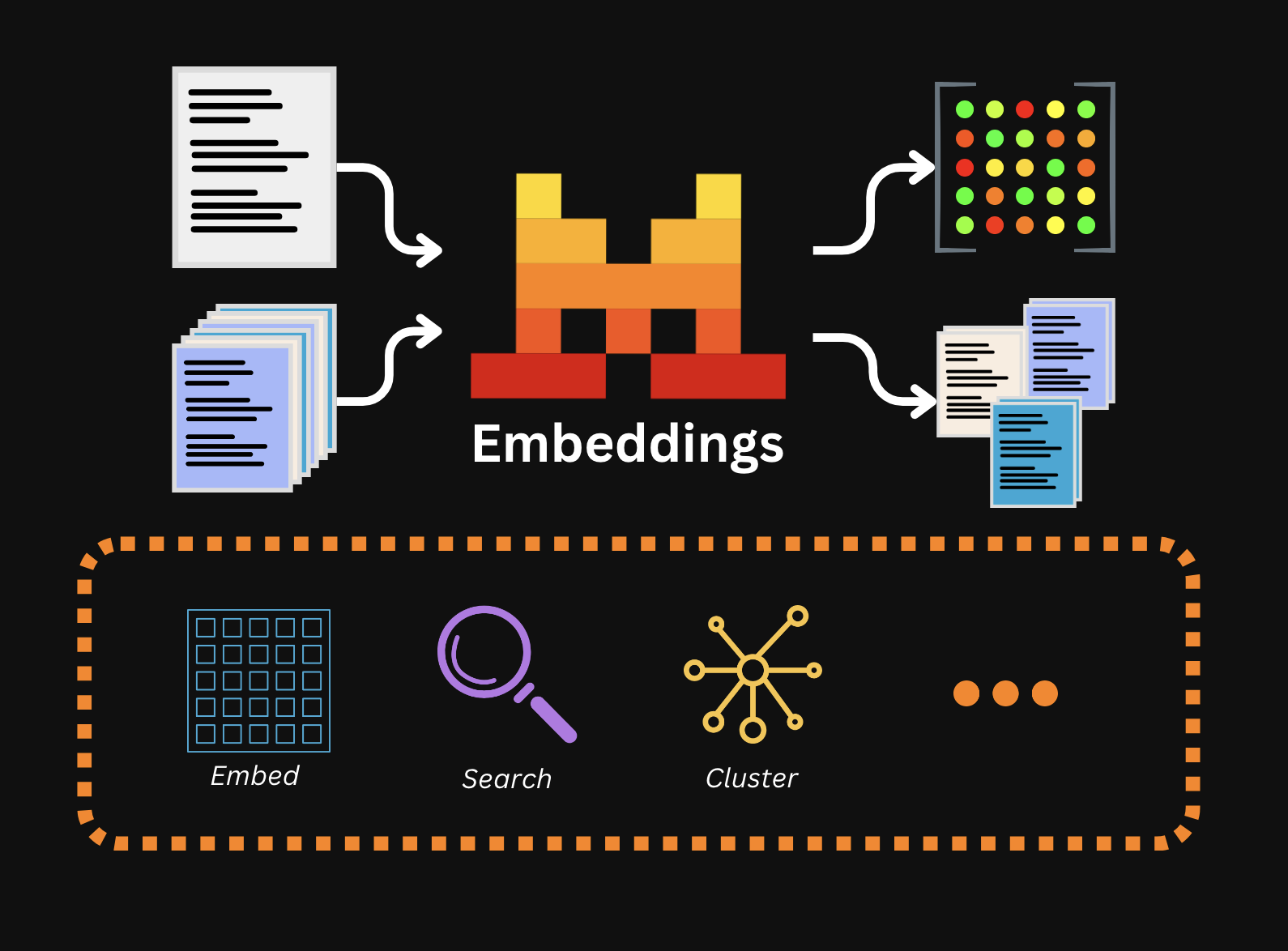

Embeddings

Embeddings are vector representations of text that capture the semantic meaning of paragraphs through their position in a high-dimensional vector space. Mistral AI's Embeddings API offers cutting-edge, state-of-the-art embeddings for text and code, which can be used for many natural language processing (NLP) tasks.

Among the vast array of use cases for embeddings are retrieval systems powering retrieval-augmented generation, clustering of unorganized data, classification of vast amounts of documents, semantic code search to explore databases and repositories, code analytics, duplicate detection, and various kinds of search when dealing with multiple sources of raw text or code.

Services

We provide two state-of-the-art embeddings:

- Text Embeddings: For embedding a wide variety of text, a general-purpose, efficient embedding model.

- Code Embeddings: Specially designed for code, perfect for embedding code databases, repositories, and powering coding assistants with state-of-the-art retrieval.

We will cover the fundamentals of the embeddings API, including how to measure the distance between text embeddings, and explore two main use cases: clustering and classification.